Review: New York Times

December 24

Book Value: The Team Spirit at Work (Rah, Rah)

By FRED ANDREWSThese four gents from New Zealand must have enjoyed themselves.

Over the course of two years, they met, among others, Michael Jordan, Mia Hamm, Joe Torre and Franz Beckenbauer, whom German soccer fans call the King. They sailed with Team New Zealand aboard Black Magic, twice winner of the America’s Cup. They went through the paces with the American women’s national soccer team, from buffet breakfast to chilling out with late-night pizza. Williams F1, the world’s pre-eminent Formula One racing team, welcomed them into the pits at the Canadian Grand Prix.

Their odyssey delivered a book, “Peak Performance: Inspirational Business Lessons from the World’s Top Sports Organizations” (Texere, $27.95), by Clive Gilson, Mike Pratt, Kevin Roberts and Ed Weymes. Except for Dr. Roberts, who is worldwide chief executive of Saatchi & Saatchi, the advertising empire, the authors are professors at the Waikato Management School at the University of Waikato in New Zealand.

The authors say businesses can learn a lot from sustained excellence in sports. They looked at nine of today’s most successful franchises, from the women’s soccer team, still fresh in the limelight, to the All Blacks, New Zealand’s national rugby team and an international force for more than a century. Great players come and go, the authors say, but excellence rests on building a “peak performance” organization that in its totality is more powerful than any player, even Mr. Jordan.

Almost none of their lessons come from the playing field. Nor does the book explain the new economics of sport or how a cunning general manager plays his cards in the confusion of college drafts, costly free agents and payroll ceilings. There are no trade secrets here.

Rather, the authors look at the shapes and styles of organizations, from secretaries and ticket punchers to presidents, vice presidents and -today’s stars- the people in charge of marketing.

The elite organizations all turn out to be small and informal, most fielding only a few hundred employees. The authors find them overflowing with secure, intelligent people who are free to do their jobs. Almost invariably, the employees say that they feel like family and laugh a lot. With thousands of applicants, the elite teams prefer loyal retainers and long-serving professionals. The San Francisco 49ers finally retired a 95-year-old usher at the insistence of his family.

The prose is visual and nicely descriptive, amazingly so for a management book by a team of authors. Anyone would be thrilled to sail with Team New Zealand, and the book brings an exciting afternoon to life. The engines roar in the Formula One pit. One wonders which author (or who else) applied the final polish. The book would be more persuasive, however, if it were not such a valentine. These glowing profiles are all self-portraits. The authors say they accumulated 4,000 pages of interview transcripts. If they spoke with a single critic, or even an independent expert, it is not apparent. So these sports tourists troop through the locker rooms with their mouths agape. They are true believers, as reverential as NFL Films.

What they offer is big-time sports through rose-colored glasses. They describe the United States Soccer Federation campaign to build up the women’s team, but not the gross favoritism toward the men’s. Even after winning the World Cup, the women’s team went on strike over their woeful pay.

The authors admire the feeling of family that Edward J. DeBartolo Jr. created by treating every 49er as a prince. They never mention his guilty plea in failing to report a felony in a gambling fraud and extortion case. That episode forced him to turn over the team to his sister, Denise DeBartolo York.

Nor do they mention Carmen Policy, the team’s president from 1991 to 1999. His genius at stretching the salary cap was considered a key to the 49ers’ peak performance. This month, the National Football League fined Mr. Policy $400,000 for violating the salary rules in those years.

A weak chapter about the New York Yankees reads like a single day’s visit. The authors describe Yankee Stadium and the streets around it. They talk in the dugout with Joe Torre. In the clubhouse, Roger Clemens has no time to chat, so they talk with Ed Yarnall, a left-hander coming back from an injury who would later be traded.

They delight to find a former receptionist’s photograph among a display of Yankee greats and to discover a half-bust in the dugout honoring an equipment manager who served 58 years. Just the right message, they say.

But their book includes this howler: “Allowing people to do their job without unnecessary interference is undoubtedly a trademark of the Yankee organization.”

Saccharin aside, the book offers an insider’s clinic on how sports are embracing big-time marketing the world over. The United States Soccer Federation orchestrated the “Road to Pasadena” matches to lift the profile of the women’s team before the World Cup. The German soccer titan FC Bayern Munich mails a million copies of its master catalog. The Atlanta Braves, described as “an entertainment brand second to none in sports,” are ever inventive and never content. The Braves were pioneers with Turner Field, a dazzling ballpark with banks of video games, a Braves museum, a retail store and a life-size baseball playground on the upper-deck roof.

Not all teams pursue the same box-office strategy. In plush times, the Chicago Bulls forcefully pushed season tickets, against the day when Mr. Jordan would depart. Only 4,000 of 22,000 seats went on nightly sale. Now in the N.B.A.’s basement, the Bulls play before thousands of empty but presumably profitable seats. FC Bayern Munich, in a soccer stadium that is much larger, limits its season tickets to 20,000 to give millions of fans a better chance ofattending a match (and, not incidentally, to sell more trinkets to a fresh audience).

The strongest chapters may be two from home, on Team New Zealand and the New Zealand Rugby Union, parent of the vaunted All Blacks.

In 1995, after a century of amateurism, potential competitors forced the rugby union to add professionals to its edifice. It created the Super 12’s league, a jazzier version of rugby, to attract new fans, particularly women, and it added the National Provincial Championship, for small-town, smash-mouth rugby played the old-fashioned way. With the All Blacks, the Super 12, the National Provincial Championship, the Black Ferns women’s team and the New Zealand Maori Team, the staid rugby union reinvented itself as a “house of brands.”

In winning the 1995 and 2000 America’s Cup, Team New Zealand went for an informal, cohesive unit that brought together all the sailors, designers, sailmakers and others, a varied lot who usually stuck to their own cubicles. Where once the cup challenge was driven by the genius who designed the boat, designers and sailors now listened to one another, the sailors clearly the customers. Instead of requiring the crew to jockey for starting berths until the last minute – which had proved very divisive – Team New Zealand announced its lineup 18 months before the event.

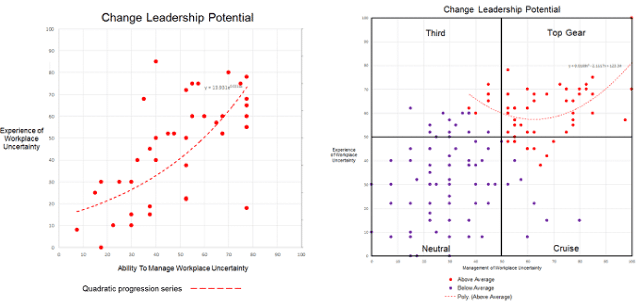

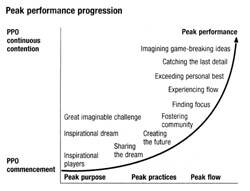

The book closes with a theory: Peak performance begins with focus, which rests on an inspirational dream and on accepting “the greatest imaginable challenge.” Peak performance also means “sharing the dream” with employees and fans. It implies an organization that feels like family, imbued with harmony, passion and flow. The final hurdle is attending to the smallest detail, inventing “game breaking” ideas and striving constantly to better the organization’s previous best.

Those virtues would transform any business. The unanswered question is how to nurture them in a business setting. These elite organizations are propelled by the joy and excitement of sport. Where does ordinary business find the equivalent?

Review: Financial Times

February 24 2000

Winning ways to stay at the top

Timing in sport, as in comedy, is everything. A Tiger Woods long iron, an André Agassi backhand service return, a Sachin Tendulkar cover drive – the sweetness of the timing provides the magic in the moment.

How the authors of Peak Performance, a new management book, must wish their timing had been better. Since Clive Gilson, Michael Pratt and Ed Weymes of the management school at the University of Waikato in New Zealand, and Kevin Roberts, chief executive of Saatchi & Saatchi Worldwide, started studying 10 of the world’s most successful sports organisations to discover what they could teach companies about success in business, several have lost their winning ways.

Williams F1, Formula One world champion in 1997, has not won a grand prix for two years.

The San Francisco 49ers of American football and the Chicago Bulls of basketball dominated their respective championships in the 1990s, but today they are among the also-rans.

Bayern Munich of football and the New Zealand All Blacks of rugby both suffered disastrous defeats in vital games last season.

Even the Atlanta Braves, baseball’s most successful team of the past decade, were humbled last year, losing 4-0 to the New York Yankees in the World Series.

These were hardly organisations performing at their peak.

These were hardly organisations performing at their peak.

Yet, Mr Gilson, in London this week to promote the book and the authors’ theory of Peak Performing Organisations (PPO), is untroubled by the calamities that have befallen so many of his chosen teams. (The four other organisations studied – Netball Australia, yacht racing’s Team New Zealand, Women’s Hockey Australia and the Australian Cricket Board – remain world-beaters.)

The Chicago Bulls, says Mr Gilson, were always going to struggle once Michael Jordan, the greatest basketball player of all time, retired in 1998.

He believes Williams F1 will be competitive next season once the car’s new engine has settled in. And the humiliating losses suffered by Bayern Munich and the All Blacks in high-profile games are not relevant because they were one-off events.

“PPO theory is not refined enough to coach to one game,” he says. “We can’t do that, but we can talk about sustained contention.”

This is the nub of Peak Performance. Sustained success in modern-day professional sport – “the most competitive domain of all human activities” – requires not necessarily the best players and coaches, but the best organisation.

“Ultimately, it is the organisation that matters. It can’t be the players because they come and go,” says Mr. Gilson.

Critics might argue that this point is undermined by the Michael Jordan experience. Before Jordan arrived, the Bulls were a bad team.

When he played, they won six championships. After he left they reverted to being a bad team. This may be unfair, though, because of the uniqueness of Jordan.

Peak Performance, a fascinating read for anyone interested in what makes sports winners tick, is not greatly interested in individuals.

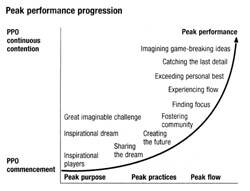

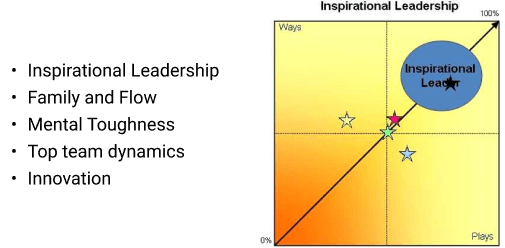

Instead, PPO theory is about three principles: peak purpose, peak practices, peak flow – and the concepts that support them.

In Bayern Munich’s case, the first principle of peak purpose consists of the “greatest imaginable challenge”(it wants to be the world’s greatest soccer club), “the inspirational dream” (it wants to win every game by more than 1-0, a dream which clearly eluded them in the European Cup final last May), and “focus” (it aims to recruit and develop the very best players).

Peak practices involve, among other things, organisations “sharing the dream” with their stakeholders, “creating the future” through good recruitment and investment, and “fostering community” inside and outside the workplace.

Peak flow involves everyone within the organization “exceeding their personal best”, “imagining game-breaking ideas” and “catching the last detail”.

Can these principles, and concepts, which are evident in some of the world’s great sporting organisations, be readily applied to business life? Mr Gilson and his co-authors believe they can.

They cite Procter & Gamble as a company that has been a peak performer for almost 50 years – 1998 marked the 43rd consecutive year of increased dividend payments.

Yet, P&G’s “greatest imaginable challenge” is to double its revenues in 10 years, which is not exactly reaching for the sky. Perhaps a better example is Saatchi & Saatchi, which under Mr Roberts’ guidance has been applying PPO theory for the past two years.

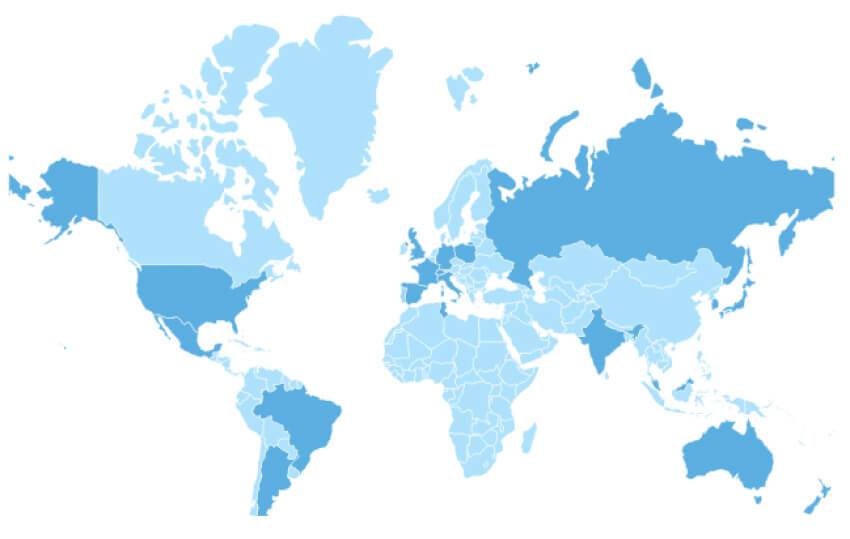

In that time, the company’s share price has quadrupled.

The attraction of PPO theory lies in its accessibility – Peak Performance is unusually well written for a management book and the theory is neatly and simply delineated – and in the attractiveness of the basic (albeit unoriginal) concept: that sport has something to teach business.

Theory aside, in the 10 organisations studied, several consistent themes emerge, such as the importance of speedy decision-making, of using key people as “inspirational players” to motivate staff, of setting and trying to exceed the highest of expectations.

The real test of PPO theory will eventually come in the business world, but it is unlikely that evidence of its success will be readily available.

But what we can do is check the progress of the book’s 10 peak performers.

If PPO theory really works, the Chicago Bulls, San Francisco 49ers and Williams F1 are going to have to recover their past form over the next two to three years.

As Sir Edmund Hillary, the legendary mountaineer, writes in his foreword to the book: “Real success is a continuing process.” Or as the old sports adage has it – getting to the top is easy, staying there is the hard part.

Peak Performance – Business Lessons from the World’s Top Sporting Organisations.

Harper Collins. £19.99.

© Copyright the Financial Times Limited 2000.

“FT” and “Financial Times” are trademarks of The Financial Times Limited.

Article: The Guardian

Guardian Saturday April 29 2000

The winning way to peak performance.

It looks like a jolly good wheeze – four men take off around the world to study organizations. And where do they find, themselves? At Bayern Munich, hobnobbing with Franz Beckenbauer and talking tactics with basketball superstar Michael Jordan and All Blacks hero Jonah Lomu. Nice work if you can get it — and come up with a management theory at the same time

That’s the background to Peak Performance Organizations (PPO) a study of successful sports teams and their consistently winning ways, on the field of play and in the highly competitive global business market.

Professors Clive Gilson and Mike Pratt, plus Kevin Roberts from Saatchi and Saatchi and Dr Ed Weymes, conclude that sport and its successful organizations have lessons for the business world. It’s about “sharing the dream”, teamwork and a way of doing things which permeates today’s management theory from other sources. PPO theory starts with the dream, vision and mission statement, and then charts the various means by which companies encourage their workforce to share this. Everyone has a common purpose: essentially, to be the best. At Bayern Munich the process begins early, with talent scouts picking the most promising players. “It’s a systematic and relentless process” say the authors, where the constant goal is to hone the skills of the best inspirational players who will secure a place in the senior national side. “Inspirational people is another line in the PPO theory: Bayern Munich has stars of the past throughout its organization.”

Beckenbauer is president of the club, Karl-Heinz Rumenigge vice-president, Uli Hoeness manager and Hans Pflugler in the merchandising department. “PPOs have inspirational players throughout, their structure,” say the authors. The concept of “charismatic leadership” is the antithesis of a top organization. It is not one person who moves things along but a series of people, whose principal function is as role models for the entire workforce.

“Everyone’s prepared to help everybody else and that’s the main thing that makes everything flow smoothly,” says Gwen Lloyd, a Bayern Munich administrator. There is no hierarchy, which assists another vital element of PPO: a free flow of information.

The team sports analogy is probably strongest in PPO when it comes to failure. Failures are not treated as matters for blame but as learning opportunities. Richard Leman, an Olympic medals winner in the England men’s hockey team, now runs Olympian Group, an astonishingly successful IT recruitment business ranked eighth in the Virgin fast-track list with a £23m turnover. “Sporting success has direct relevance in the business world,” he says.

Making a mistake is a chance to learn, he insists. He also takes the view that businesses need to create an environment where people want to work. His own new recruits are made part of a team from the outset. “We have openness and fairness”, he says “And very little hierarchy. As In a team, there is no room for egos.” Office politics are out. The team spirit creates a nurturing environment which in turn advances the business, says the authors. In a company culture where there is free flow of information, teamwork, an absence of hierarchy and ego, and no stigma attached to failure, staff can advance creative ideas both individually and collectively. “There is an enthusiasm for risk because innovation gains recognition and credit,” the authors say. “Innovation often goes through considerable periods of failure before success is arrived at. Innovation and game-breaking ideas flourish in this atmosphere because there is no fear of failure.”

PPO’s authors took their theory and tested it against the practice of Proctor & Gamble -described by them as the consummate corporate peak performer. The company collaborates with suppliers and enhances its expertise by increasing the knowledge and creativity of the business partners who provide the raw material for their products.

The authors have collated the work into a usable theory for other managements to follow. It may be a little evangelical in tone but it has worked to stunning effect for the subjects of the research.

Peak Performance Organizations, Harper Collins, £19.99

Review: The Independent

2nd February 2000

By: Richard Surface

Book of the week – Business tales, with a sporting chance of success

AMERICAN BUSINESSMEN have long been derided on this side of the Atlantic for their use of sports metaphors. “We’ll end-run ’em” (translation: new approach that avoids head-on competition); “pinch-hit” (stand-in for the man just fired); “drop back 10 yards and punt” (think again). If, as the authors of Peak Performance claim, the application of sports metaphors to business issues is on the rise, yet another US export to Europe is at hand. The blessing will be as mixed as the metaphors.Peak Performance combines case study analyses of 10 world-class sports organisations with a theory about their business success. This theory is called “PPO”, for Peak Performing Organisations, and is elaborated under three headings, purpose, practices, and “flow” (how people work together), all activated by inspirational players. Apply what a top sports enterprise does to your business and you, too, can become a peak performer.

Well, yes – and no.

There can be no doubt common threads run through different forms of organised human effort, and analysis of one area can shed light on others. The scientists Crick and Watson’s search for the DNA structure has commercially useful lessons. But such lessons can cut both ways: The International Olympic Committee presumably benefited from running the 1984 Los Angeles Summer Games, which was organised for the first time as a business activity.

On a day-to-day level, the use in business of analogies from sport – or military or science – derives from the need to inspire. “We’re going to take that hill, men!” or simply, “Let’s be winners!” are more likely to start the juices flowing than, “I think it would be jolly nice to increase market share this year”.

But sport’s ability to generate emotion undermines the authors’ argument that key success factors in sports organisations can apply to business. People are more readily inspired by sports than they are to most commercial businesses. Women join Netball Australia, and marketeers queue to work for the Chicago Bulls because of an overarching passion for the games they play.

In contrast, most people join a company on substantially lower commitment – let alone passion – levels. Their first priority is a job, a living wage, maybe becoming rich, or simply wanting to live in a particular part of the world. It is all very well to urge chief executives to generate passion in their staff toward the business and its products, but how? If the authors answered this question, I missed it.

The reality is that staff are not fooled by overstretched analogies and efforts to make the organisation’s purpose grander than it is. Did Ray Kroc, acknowledged leader of McDonald’s spectacular rise in the Seventies and Eighties, really believe that to work beneath the Golden Arches you “had to see beauty in a hamburger bun”? I doubt it. And in business, heretical as this may sound, the “passion-thing” can be overdone.

In a 200-to-300-staff Formula 1 constructor organisation, consistent outperformance demands that all employees share the dream to a messianic degree. But large businesses can prosper with a committed vital few, a core-talented minority in pivotal roles, especially if competition is weak.

There is a deeper level at which sports/business analogies break down. In sport, the team practices, and practices, and practices – then plays. In business, the game is every day. Business “practicing” is done in tandem with the game-playing and usually with a tenuous causal relationship to long-term success. There was a famously successful US college basketball coach who said: “There’s no such thing as the `will to win’. There’s only the will to prepare to win.”

On a more detailed level, most of the findings in this book and their relevance to business ring true, even if they have been said before. But with 200 of 300 pages dedicated to sports stories, Peak Performance may actually be read by many who buy it. The most irritating aspect of this book is its unabashedly eulogistic tone. No chinks, no faults are discovered. At peak-performing enterprises everything is done well – not only by the sports organisations. Proctor & Gamble serves as the corporate guinea pig for testing “PPO” theory. The results are summarised in 15 pages of sycophantic prose. Most businesspeople would be less impressed than the authors by the following: “The greatest imaginable challenge [at P&G] is based on `the passion for winning’ – is to double [global revenues] in 10 years.” That target represents about 6 to 7 per cent growth per year, hardly calculated to send the stock market into a P&G feeding frenzy or to inspire staff to Herculean efforts. This tendency to overpraise undercuts parts of the book which a reader may know about.

In my case, this is Formula 1. The paean of praise heaped on the Williams team neglects to mention the potentially damaging impact on good drivers. If the car is king at Williams, and drivers take a back seat, this may partly explain why Heinz-Harald Frentzen performed poorly at Williams in the 1998 season and superbly last year at Jordan. These cavils aside, you have to wish this book well and expect it will be, ahem, a winner, despite the publisher’s poor marketing decision to hide the 10 sports teams’ logos on the back cover. But it will be enjoyed rather more by sports fans who have jobs than by businessmen seeking guidance.

Richard Surface

The reviewer is a former managing director of Pearl Assurance.

Review: The Daily Telegraph

By Simon Hughes

Talking Sport: British heroes can inspire the troops

WHY is the Australian cricket team so consistently successful? How has a titchy nation like New Zealand left the world’s might trailing in its wake on the water, and managed to win an astonishing 72 per cent of all its rugby internationals?

Two fifty-something Lancastrians have unearthed the answers, and in so doing offered some possible solutions to our own sporting problems.

These are not ordinary Lancastrians. Dr Kevin Roberts is the chief executive of Saatchi and Saatchi worldwide, and Professor Clive Gilson is an expert in resource management. They and two other Englishmen, Mike Pratt and Ed Weymes, have produced Peak Performance (Harper Collins Business, £19.99), a book which delves behind the great sporting teams of the last 20 years.

Seeking new motivational techniques for business, they analysed the management and structures of consistently high-performance units such as Bayern Munich, the Williams Formula One team, the Chicago Bulls and the Australian cricket team. As all four authors are affiliated to the Waikato Management School, a southern hemisphere Harvard, they were also ideally positioned to analyse New Zealand sport.

They drew a number of striking conclusions:

1) All the organisations have at their heart highly inspirational people. Franz Beckenbauer is president of Bayern Munich; Rod Marsh runs the Australian cricket academy, and Sir Donald Bradman is regularly consulted; Andy Dalton, the great All Blacks captain, is president of the NZ Rugby Football Union.

In comparison, most phenomenal British team players (Ian Botham, David Gower, Gary Lineker, Bill Beaumont) end up in the media. Our sporting organisations tend to be run by visionless nonentities. “They’re comfortable with mediocrity,” says Roberts.

2) They cultivate a spirit of total focus and harmony. Everyone in the organisation, from the chief to the chef, buys into what the authors call “the greatest imaginable challenge”. This might sound like psychologist’s jargon but, throughout, these teams are clear about their ambition: Sir Peter Blake, head of the Team New Zealand yachting syndicate, says: “Coming first may not be everything but coming second is nothing.” Denis Rogers, chairman of the Australian Cricket Board, adds: “Australian cricket never loses sight of its prime purpose, to win every international match.” They’re sticking to their manifesto, having won 20 of the last 22.

3) They constantly wheel in former greats for motivation, and concentrate on improving their own assets rather than worrying about the opposition. Before a recent one-day international against New Zealand, Australian coach John Buchanan gave his players a piece of paper listing the strengths and weaknesses of all 11 opponents. Each one had 20 flaws and no strengths.

4) There is a clear “stairway” to the top, enabling talented amateurs to progress to full international status in a few well-taken steps. It fosters national support. Amateur sport in Britain is generally a cul-de-sac. The professionals live on an inaccessible plateau. It breeds parochialism.

Roberts values inspiration over leadership, and condemns multi-layered, hierarchical institutions, and Britain’s “tall poppy syndrome” – knocking stars off their pedestal if they get too lofty. Using his three-point model – aim for the stratosphere, synchronise your aims, build a pyramid to reach them – he has transformed Saatchi and Saatchi and the share price has quadrupled in the last 18 months. He claims he can perform the same upgrade within three years on various British teams. But how many would buy into the do-you-really-want-it-sir philosophy?

These were hardly organisations performing at their peak.

These were hardly organisations performing at their peak.